13 Rules for Making Useful Flashcards

Sukhans Asrani

Founder @ Zorbi

Making useful flashcards is a skill that seems daunting at first, but the good news is that anyone can develop it. This guide gives you a list of thirteen simple rules that will help you make great flashcards.

Absorbing these rules will completely change the way you approach learning. If this is your first time learning how to make great flashcards, you'll be amazed at how fast you can absorb and retain information.

This guide provides:

- A simple test for figuring out if your flashcards are bad

- Memorize this and you'll know when to re-read this guide.

- Thirteen rules you should follow when making flashcards

- If you're new to flashcards, then pay attention to Rule 10 (Don't forget to cloze), Rule 4 (Avoid complex cards) and Rule 7 (Avoid lists)

Is it painful?: A test for bad flashcards

Answer the following questions honestly:

- Do you find yourself constantly forgetting flashcards?

- Does it feel like studying 5 cards is painful?

If you answered yes, then there is a good chance that your flashcards are bad.

Read the following 13 rules and redesign your flashcards. Your learning speed will accelerate beyond what you thought was possible.

The Thirteen Rules

1. Don't learn things you don't understand

Learning facts from a medical textbook when you've never studied biology is a good way to make yourself miserable.

Although you might be able to rote-learn these facts and pass an exam, it'll take far more time than it would have taken if you had existing foundational knowledge on the topic. It's better to gain an understanding of the basics before using flashcards.

2. Get an overview first

Learning from a flashcard deck without an overview of the topic will mean you can't connect ideas together.

You should start by watching/reading an overview of the topic which will connect ideas together and then proceed with testing yourself using individual questions and answers.

3. Don't ignore the basics

Sometimes people think they shouldn't create flashcards for basic concepts, but the cost of forgetting the basics is much larger than the cost of occasionally reviewing them.

You should still create flashcards for basic concepts. Don't worry about wasting time, Zorbi's spaced-repetition algorithm will schedule easy cards months away after you've answered them a few times.

4. Keep It Simple Stupid (KISS)

Simple, small, and direct questions are easier to answer than complex questions.

A lot of people that are new to spaced-repetition will create flashcards that contain too many points because they want to reduce their time doing reviews. Creating many small questions will actually cause you to 'fail' cards less often and you'll end up saving time.

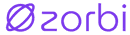

The following is an example of a complex card

You could isolate each of those characteristics and break them into separate flashcards.

- Where is the Dead Sea located? :: on the border between Israel and Jordan

- How long is the Dead Sea? :: 74km

- Where does the 'Dead' in Dead Sea come from? :: only simple organisms can live in it because of the salt levels

Take note of how short and concise each of those questions and answers are.

5. Use pictures

Our visual processing power is far superior to our verbal processing power - that's why they say a picture is worth a thousand words. Using images, flowcharts, and diagrams can make concepts significantly easier to remember.

Most business students will have to learn and memorize Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs:

The flashcard with the pyramid is going to be easier to remember. But in this case, both cards aren't that great. You can improve on this card by adding a word or acronym mnemonic - see rule 6.

6. Use mnemonics

Mnemonics are techniques that make remembering things easy.

You might have to force yourself to use mnemonics when you first get started, but over time you'll find yourself doing it automatically.

Some examples of mnemonics include:

- Acronym Mnemonics

- Combine the first letter of each word into a new word or acronym.

- Example: ROY G BIV — The colours of the rainbow (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet)

- Sentence Mnemonics

- Where the first letter of each word is combined to form a phrase or sentence

- "Richard of York gave battle in vain" for the colours of the rainbow

- Model Mnemonics

- Using a mindmap, diagram, or graph to help you memorize an idea

- Example: Maslow's hierarchy of needs from the previous question is always represented as a pyramid

- Visualization Techniques

- Creating memory associations using images or visualisations

- For example you 'walk through' a memory palace in your head to remember information.

7. Avoid lists

The cost of remembering a list is brutal and you should avoid them in your flashcards. This rule is especially applicable to any unordered lists.

Unfortunately, lots of areas in academia force you to remember lists of information. If you find yourself in this situation then turn it into an ordered list if you can (e.g. alphabetical order) or use a sentence/acronym mnemonic.

8. Personalize

One of the best ways to make flashcards more memorable is to link them with something you already remember. You can do this by adding an example from your life or making mnemonics more personal.

When forced to memorise lists, I'll use the names of my friends in mnemonics to make them easy to remember.

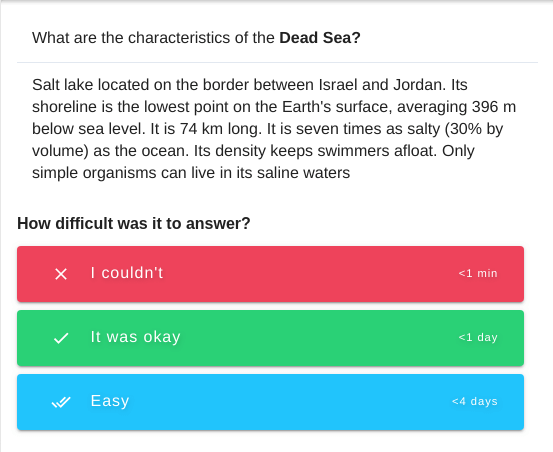

For example, I might have something like the following card:

Note: The two U's in the list make this card risky and hard to remember, which is why lists can be bad. If this was an important card to remember, I would also use cloze deletions (rule 10) or images (rule 5) to guarantee that I remember it.

9. Use Examples

This rule is closely related with the previous one. Adding examples to cards can greatly reduce your learning time, especially if they are personalized.

10. Don't forget to cloze

A cloze deletion, or a cloze, is a sentence where a part has been removed and replaced by three dots.

I've found that creating clozes is the fastest and easiest way to convert my notes into learnable flashcards. It's extremely easy to copy a sentence from a book and then remove a part of the text.

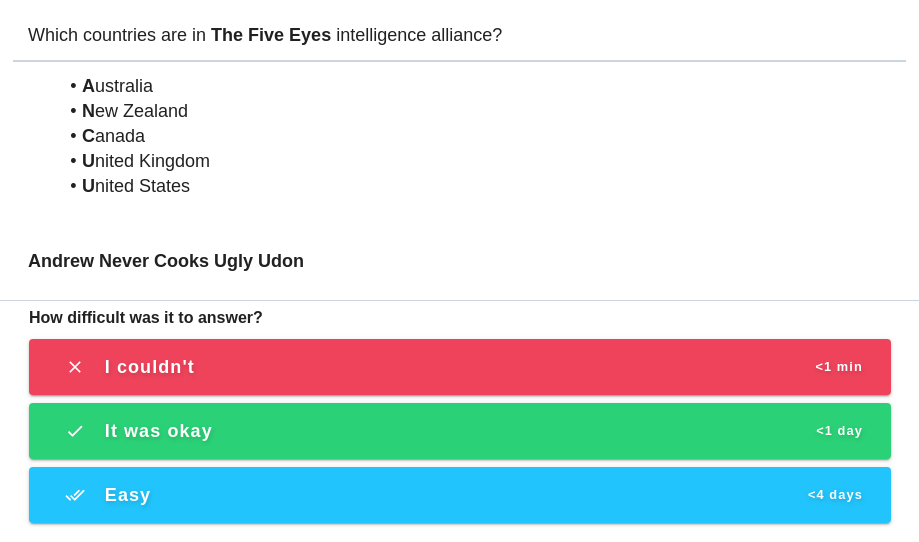

Rookies will often make expensive flashcards like the following:

A quick and easy way to turn that card into a good set of flashcards would be:

- The ... is an intelligence alliance comprising Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

- Five Eyes

- The Five Eyes countries are parties to the multilateral ..., a treaty for joint cooperation in signals intelligence.

- UKUSA Agreement

- The UKUSA Agreement is a treaty for ...

- joint cooperation in signals intelligence

- The origins of the Five Eyes can be traced back to the ... that was issued by the Allies to lay out their goals for a post-WW2 world.

- Atlantic Charter

- The ... can be traced back to the Atlantic Charter that was issued by the Allies to lay out their goals for a post-WW2 world.

- origins of the Five Eyes

Although that breaks a single flashcard into five cards, you'll end up learning the content significantly faster and you'll be less likely to forget a card. With spaced-repetition, the costs and probability of forgetting a bulky card is much higher than smaller and simpler cards. (See Rule #4 - Keep it Simple Stupid). You might have also noticed that the last two cards test the same idea, this is known as using redundancy (rule 11), discussed right below.

11. Use redundancy

The idea of "redundant information" relates to creating cards that look like they're duplicating information or adding more information than needed.

Some people think this contradicts Rule #4 (Keep Things Simple) but it can help with learning. Here are two few examples where redundant information can help:

- Attack with different angles:

- This one is most common when studying languages. If you're learning Spanish, then you might be able to remember that phone is teléfono but you may not remember it the other way around (that teléfono is phone). So make cards for both translations!

- For other complex knowledge items, you also want to represent it in multiple ways. Memorizing different representations of a fact is recommended when the fact is important (or you keep forgetting it even while following the other rules in this guide).

- Derivation Steps:

- If you're learning something complex like a mathematical proof then you should also memorize the steps taken to derive that proof.

- Note: This isn't rote-learning. There is science backing the use of spaced-repetition for complex maths. It's the fastest way to teach your brain what the correct path is when solving a problem.

- Handle Equivalence:

- Don't punish yourself for getting a flashcard wrong just because you gave the wrong "form" of the answer.

- When learning languages, this can often apply to synonyms (unless the context of the card makes that synonym wrong).

12. Add context cues

You can stick to Rule #4 - Keep it Simple Stupid while adding extra info that explains the answer.

When learning university subjects, I liked screenshotting the lecture slide to add extra context to the card. Sometimes I would also merge this with Rule #8 — Personalize and reference some knowledge from another subject/topic that had an overlapping element.

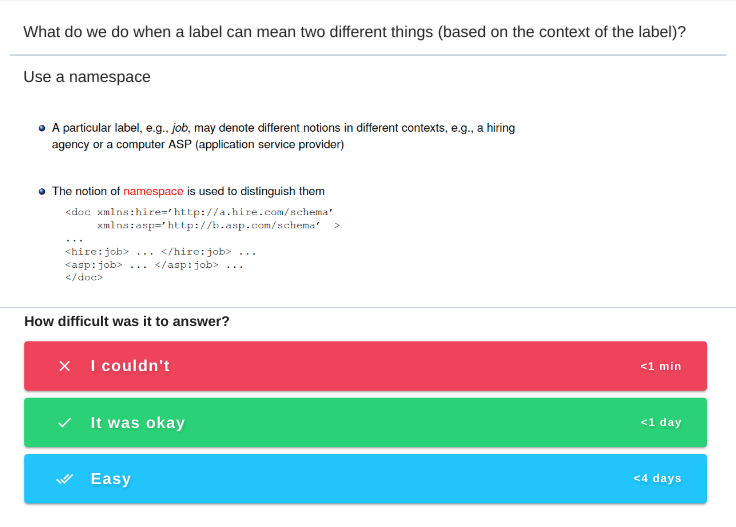

Here is a real flashcard from a university paper where we were learning about a programming language called XML:

Although you might not know anything about XML, it should be clear how this is a good flashcard. It has a simple question, a simple answer, and a screenshot of the relevant part of the lecture slide. The screenshot provides enough context for me to refresh my overall knowledge on this fact.

13. Add Sources

For complex flashcards, it can also be useful to add the source of the information.

You won't need to do this often since screenshots of the area are usually enough, but you can add specific page numbers of textbooks or links to websites to your cards.

And that's all - thanks for reading. If you get anything out of this then I'd recommend memorizing that "Is it painful?" test at the start of this guide. The test should act as a reliable signal for when you need to re-read this guide and update your flashcards.

Sources: